Clara Oswald: A Study of the Impossible Storyteller (Part 2)

Guest contributor Ruth Long continues her tribute series looking back over Jenna Coleman’s companion.

- Catch up on A Study of the Impossible Girl

- Catch up on A Study of the Impossible Mirror

- Catch up on A Study of the Storyteller: Part 1

As we look back on her final act, I wanted to pay tribute to the companion that has defined and driven my experience as a fan of the show. ‘A Study of the Impossible’ is a series of articles examining the character of Clara Oswald. In each chapter, we will be exploring the Impossible Girl in her journey with the Doctor: from the moment she set foot in the TARDIS, to the day she bade us farewell. This fourth installment (Chapter 3 Part 2) will predominantly focus on the middle of Series 9, though naturally, there will be references made to her entire tenure.

I came into Series 9 with definite expectations concerning Clara’s characterization: envisioning a continuation in the prominent development and direct focus of the previous year, albeit with a shift in emphasis away from her Earth life. Because of this, I initially found myself to be somewhat disappointed. The writing and acting was superlative as ever, but I was taken aback that, especially compared with Series 8, Clara was often restricted in her agency; or even removed from the picture entirely. It was an unexpected change in approach that I admittedly had mixed feelings about.

As the episodes progressed, however (and with the helpful interpretations of fellow fans), I soon came to a realization. A character’s presence can be heard all the louder in their absence, and likewise their vulnerability can be used to accentuate their capability. This series didn’t rest on the same overt means of exploring Clara; it instead chose to tackle aspects of her that can only be perceived by taking her story out of her hands. By extension this posed an intriguing question: When you’re the author of your own grand narrative, can you dictate your legacy? Or does that fall to the influence of others?

Lost in space, seconds from asphyxiation, brushing with death: Business as usual. Veteran time-travelers concluding their latest (off-screen) adventure, the Doctor and Clara function in masterful simpatico. Barely escaping dangerous exploits is par for the course; the latter doesn’t even breathe so much as a ‘Thank you’ to her rescuer, turning her attention immediately to the task at hand (“How did we do? What about all the Velosians? Are they safe?”). This is how we commence ‘The Girl Who Died’: in many respects the most significant episode of the series preceding the finale. The ripple that will soon become a tidal wave…

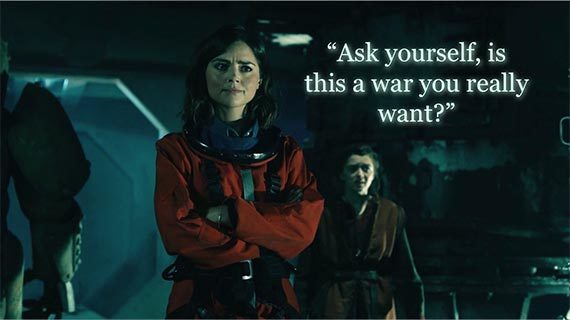

Though the obvious function of this story is the genesis of the immortal ‘Me’, it’s ultimately a contemplative study of our two leads. Early on the ‘companion’ is separated (by her own doing) and placed centre-stage for a performance traditionally reserved outside of her designated role (but when has that ever stopped her – or her predecessors?). An adept negotiator in her own right, Clara confronts ‘Odin’ with all the wit, cunning and tenacity of the Doctor; accompanied by a measure of aloof ‘Time Lady’ detachment – speaking in a pretty inconsiderate manner before a horrified Ashildr (“So you mash up Vikings to make warrior juice, nice” “They what?!”).

Equally notable is that she holds herself with a confidence and superiority entirely her own: there’s no need for the “Clara Oswald has never existed”-style masquerading and deception anymore. Using words as her preferred weapon of choice (complete with quips – “Time for your medication?”), her endeavor to gain the upper hand and ‘save the day’ (warrior casualties aside) would have even succeeded save for the impertinence of the young girl who accompanied her. The Doctor assumes so, such is his assurance in her ability: “did you persuade them to go? I knew that you would”. Indeed, this is Clara at her most daring, brilliant and candid… and it’s terrifying.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to make you afraid”

He should be.

At its midpoint the plot pauses in a calm before the storm, mechanical thunder resounding in the distance, for a moment of reflection. The Doctor’s thoughts are not only on the battle ahead, however. “Turning them into fighters? That’s not like you” “Yeah, I used to believe that too” Perhaps there is a quiet whispering in the back of his mind; a voice of triumphant, malevolent accusation:

“The Doctor’s soul is revealed. See him. See the heart of him. The man who abhors violence: never carrying a gun. But this is the truth, Doctor. You take ordinary people and you fashion them into weapons. Behold, your children of time.”

This is his own fault. His face is etched with the same troubled regret worn when he uttered that goodness “had nothing to do with it”. “Oh Clara Oswald, what have I made of you?” he laments… Now it’s Clara’s turn to respond with emotional avoidance (as she did in their last exchange of this nature); a look of discomfort, stubbornly clinging to the false idea that the life she’s addicted to, the thing that has given her “something else to be,” is just a hobby. The control-freak firmly out of control: running faster, fighting harder and more truthful than ever, yet still unable to admit certain things to herself. Because the Doctor is wrong: The woman in front of him isn’t, and never was, of his creation.

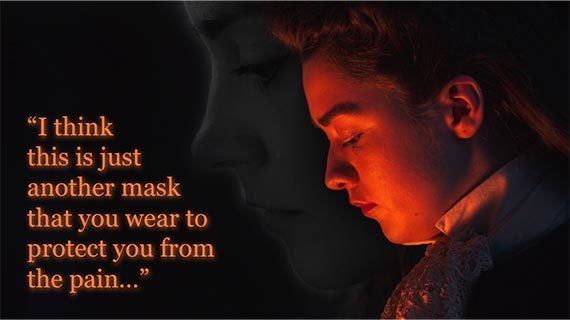

Leading on, we soon encounter the fundamental theme of mortality and immortality. This concept is most clearly illustrated in the form of Ashildr, or ‘Me’ as she comes to call herself; who by way of her arc becomes a lens through which we can scrutinize our main duo. ‘The Woman Who Lived’ is ostensibly an episode that has very little to do with Clara at all, yet she casts a heavy shadow as the unspoken third person in this character piece. Within such a trine of figures, Me is both reflection and contradiction. She stands as an obvious parallel to the Doctor, but equally so with Clara.

Two women who compose their lives into storybooks; some of the pages scarred with tears. One does so quite literally to preserve what she dares to remember, the other beyond the binding of the physical so that she’s never truly forgotten. Two women who invite the Doctor’s fear and guilt: capable of being cold and merciless in their conviction. One consumed by a bitterness and emptiness of his doing, the other the frightening maker of herself. Two women whose perspectives are too vast and far away; to which death can be boring and the Earth much too small. One seeks liberation from the cage of forever, the other chases the universe though deep down she knows it can’t last.

When Clara does finally appear in person, she’s a welcome juxtaposition to the weariness of two immortals. Gazing in ceaseless wonder at the whirring lights above, she still possesses the same childlike awe and lust for adventure that she’s always had; untouched and untarnished in spite of everything (“Oh, that noise! I never knew how much I loved it!”). The whole scene harkens back to the excitement of her first true trip in the TARDIS: pacing around the console, the pendant of a bird hanging from her neck, an eager grin written on her face: Where to go? What to see? “Somewhere magical” “Something awesome”.

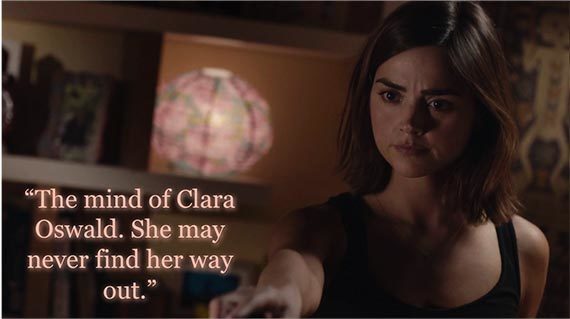

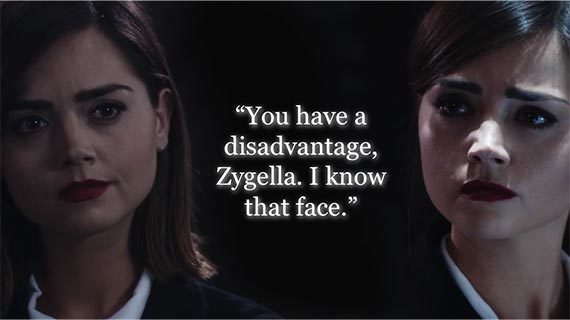

If Me illuminates certain sides to Clara, then Bonnie clothes them in darkness. Fascinatingly, she doesn’t merely exist as a metaphorical representation, but actively robs Clara of her identity; wearing her face as a façade and in doing so exposing the deepest cracks in her persona – at great irony. Furthermore, the premise examines our perception of the character and that of those around her: the intricacies of her disposition, what we expect her to be. Essentially, in allowing an antagonist to assume her guise, the Zygon two-parter becomes a meditation on who Clara is; her potential for monstrosity, the internal conflict of her psyche and above all, the impression she leaves in her stead.

If you wish to infiltrate UNIT, who better to impersonate than the woman the Doctor trusts implicitly, the one everyone just waves on past? Who by account of her ego will cheat at board games and whose penchant for acting strangely will arouse little suspicion? The presentation of ‘The Zygon Invasion’ carefully walks the line between what we’d consider typical Clara behavior and that of the vengeful alien portraying her; it’s surprising how thin that line can be. In fact, on both of the occasions that she is eventually discovered, the realization comes far too late. That’s not to say that the clues aren’t there, but with every glaring discrepancy there’s just enough uncomfortable truth to soften the deception.

Meanwhile, at fault of her own compassion, the real Clara Oswald is once again confined to a dream-like world. The situation is highly evocative of Oswin; who though physically incapacitated (to say the least), used her mind to fabricate a miniature reality from which she fought for her identity; “trying to take control, piece by piece”. In making this connection we’re also reminded of earlier in the series, where Missy forces her to relive a traumatic echo of that other life, and by doing so denying her autonomy. Placing Clara in these positions tests her in ways we simply can’t observe when she maintains sovereignty over her circumstances.

Refusing to surrender under Bonnie’s duress, Clara thwarts her with ingenuity and sheer strength of will: The furious inner fortitude that withstood a Dalek conversion, melted a frozen army and survived shattering into a million pieces doesn’t back down easily (“Having trouble? Let’s see what I can do”). Though if there is one person who can truly challenge Clara, instill her with undeniable fear, it’s someone of her likeness. Their battle for control is, symbolically, a confrontation with herself. Threats of death meet the usual defiance (“Go on then, do it”), but suppress her ability to speak or take away her lies, and audacity gives way to unease. Of course: to scare a storyteller is to wrench the pen from their grip.

Beat for beat; their hearts linked. Now she must rely on her wits alone, a gun to her head and no way to escape. Applying the bold intellect worthy of a rebel Time Lord, she tells Bonnie just enough to prolong her life: tipping the scales in her favour (“You’re going to want to speak to me again”). Clara smiles, ending their showdown as its captive victor (“See ya later!”). But this figurative struggle of self preludes a significantly greater encounter; one in which she’s a central participant, the recipient of heartfelt appeal, the gentle voice of influence… and she doesn’t say a single word.

The friend inside the enemy, the enemy inside the friend: everyone’s a bit of both. A human can be a monster, a healer can cause destruction, a savior can betray. The Doctor’s impassioned speech is a wake-up call to the world, an outpouring of wisdom gained through harrowing experience, but the spectacle is also a powerful allegory of a deeply intricate relationship. Poised, ready to do the unthinkable: a box, a button, and no other way. But in the shake of a head, in a single, imploring look on a young woman’s desperate face, another way is found. Now, an inversion: the same man, staring into the same face. It’s time for him to convince her to “be a Doctor”. Clara Oswald stands by as witness, and student, to her own legacy.

Join us next time for Part 3, where we’ll be following Clara throughout the finale of Series 9…